Rewriting the Story of Everest: The Overlooked Role of Sherpa Expertise

The history of Mount Everest climbing has mostly been relayed as accounts of British and European daring and triumph, particularly throughout the early and mid-twentieth century. But the reality is far more nuanced and many of the early narratives are layered with imperial ambition, forgotten stories, and the tacit expertise of Himalayan peoples.

As a global adventure travel company, we couldn’t function without the knowledge and capability of local experts. The sherpas and porters who work with us are central to our operations and the safety we provide to our trekkers on the mountains. At Kandoo, we’re fascinated by what has shaped the history of trekking and climbing, and looking back at a century of recorded Everest climbing history, an overall bias towards celebrating European summiters becomes apparent. However, their success wouldn’t have been possible without the support and expertise of the sherpas and porters who were part of these expeditions.

Here, we look at a timeline of a century of Everest climbing, some of the key dates, the narratives surrounding them, and how sherpas have been central to the success of these momentous climbing events. We give particular attention to the earliest expeditions, as they established the foundation for all subsequent attempts and are also the events with the most overlooked Himalayan input in commercially available accounts.

1921 - 1924: Research, Mallory and Irvine, and early Everest summit attempts

1921 - The British Reconnaissance Expedition

Everest got the attention of the British after World War I, who set out to frame the mountain as the “last great conquest” of the empire. This first expedition is sometimes incorrectly referred to as “The Mallory and Irvine research expedition”.

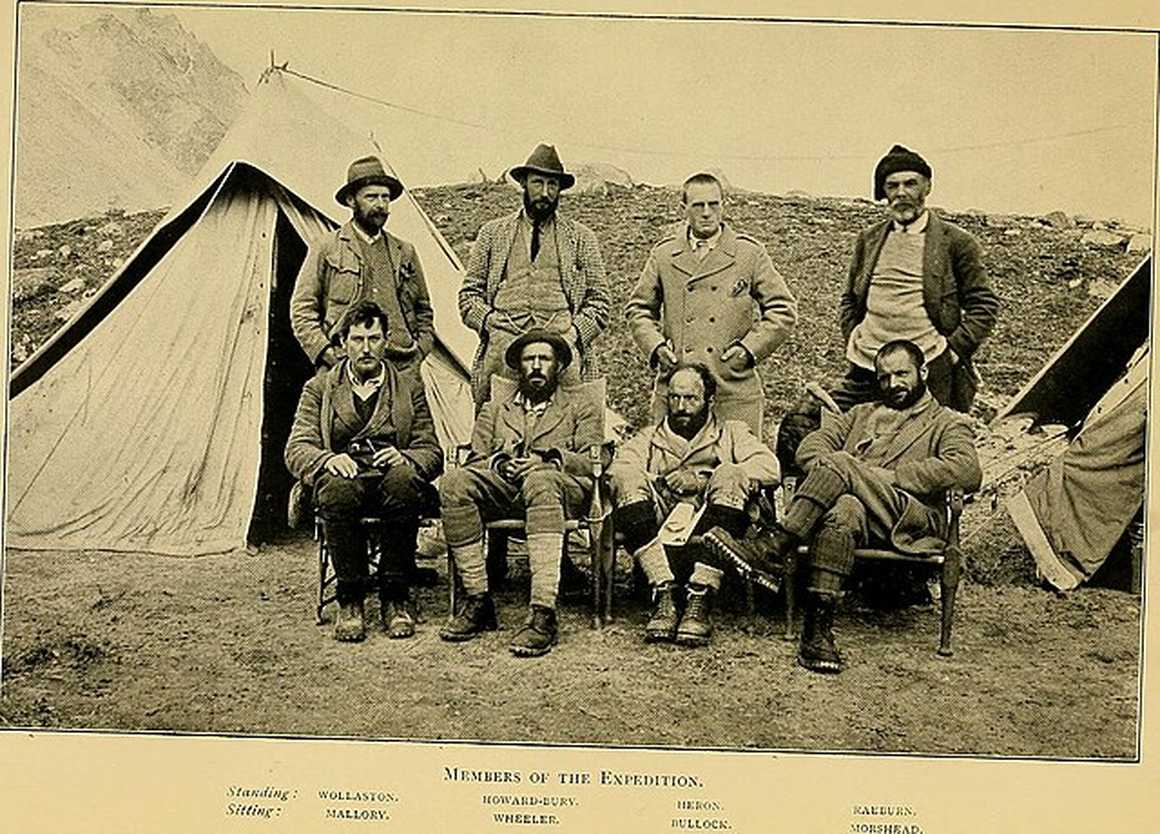

Irvine wasn’t involved in any expeditions until 1924, and it was actually led by Charles Howard-Bury, with climbers including George Mallory, Guy Bullock, and surveyors such as Alexander Kellas (who died en route). The expedition entered Tibet as Nepal was closed to foreigners at the time.

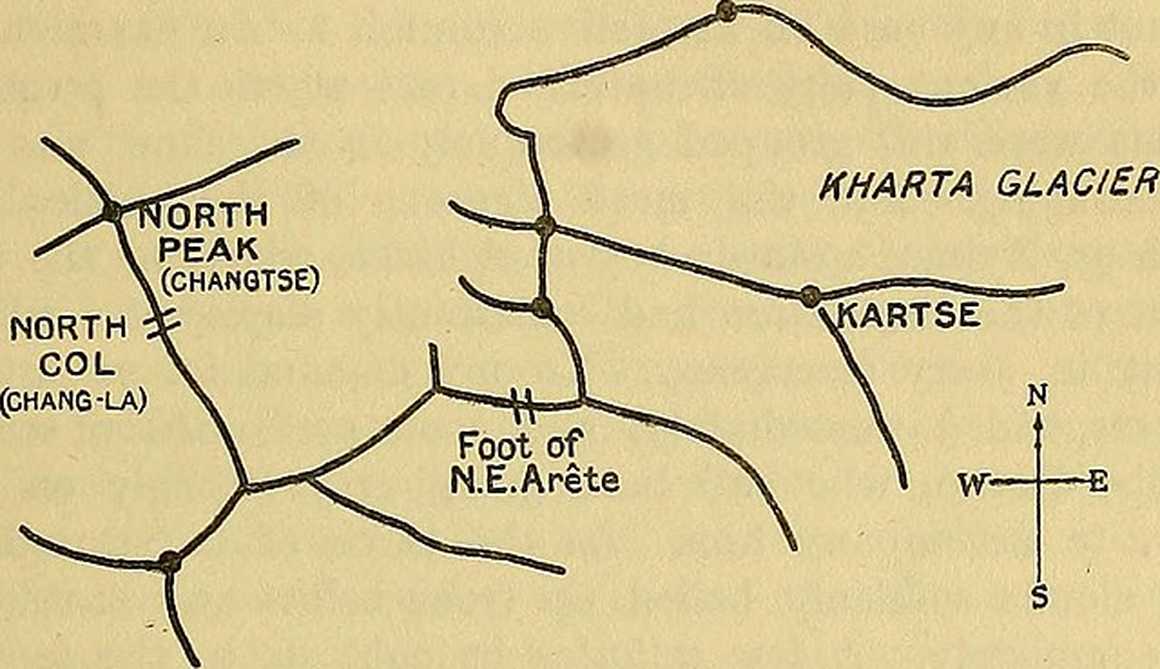

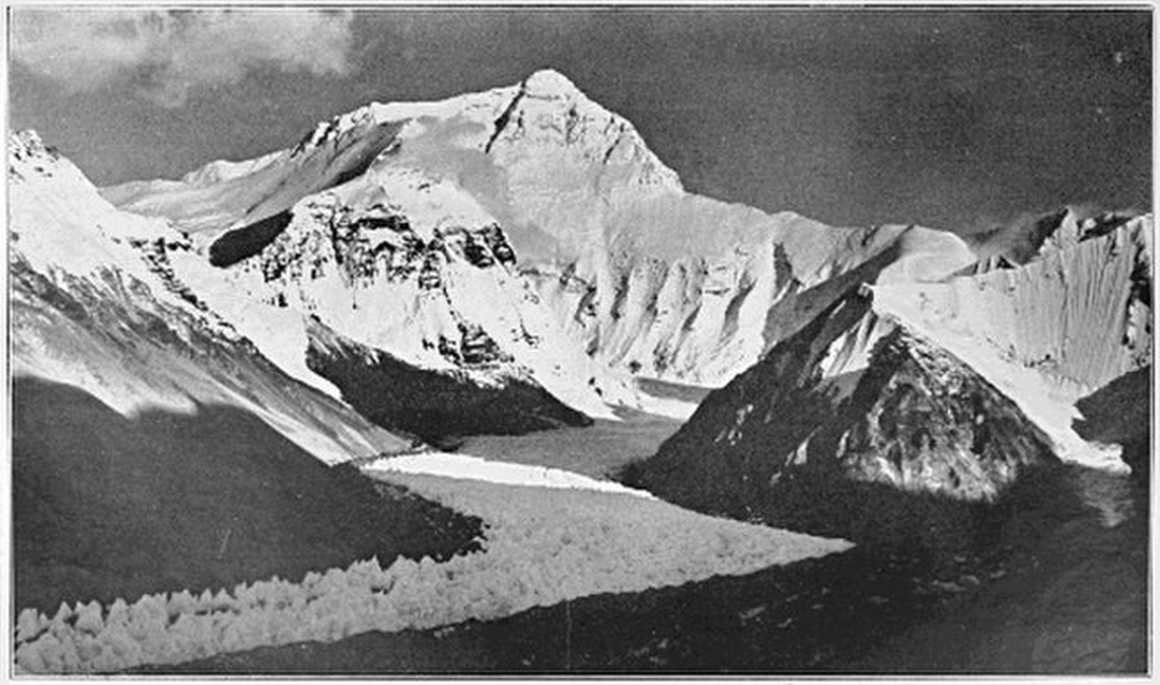

The team mapped Everest’s northern approaches, identified possible climbing routes via the North Col, and reached altitudes of around 7,000m. No summit attempt was made, but the expedition provided critical cartographic, geological, and photographic data, establishing the foundation for all subsequent Everest expeditions in the 1920s and 1930s.

1922 - The First Major Climbing Attempt of Mount Everest

Led by Charles Bruce with Edward Norton and George Mallory among the British climbers. The 1922 expedition was the first attempt at the summit, with the team using supplemental oxygen to bolster them. They reached a record altitude of 8,320m, the first time humans climbed above 8,000m.

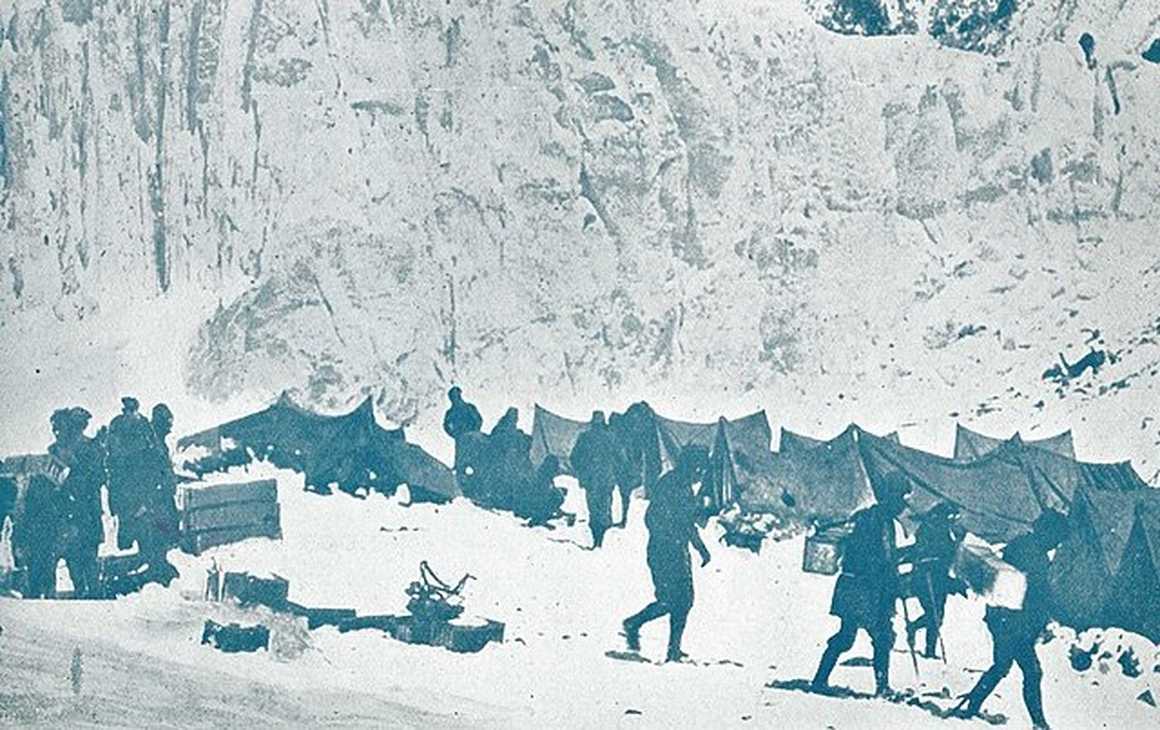

These early expeditions relied heavily on Sherpa and other Himalayan porters for their logistics.

Archival records show Sherpa labour included:

- Provisioning and portering

- Guiding and piloting

- Identifying and collecting

- Interpreting and negotiating

- Sheltering and protecting

- Transporting scientific equipment, tents, oxygen sets, and even film cameras to extreme altitudes.

The system used to recruit Everest Sherpa mirrored colonial military service at the time, with thumbprints replacing signatures for wages or death compensation.

Tragedy struck during the 1922 expedition when an avalanche killed seven Sherpas and porters. Those killed in the avalanche were named in committee records as: Dorje, Lhakpa, Norbu, Pasang, Pema, Sange, Temba, yet their identities were largely erased from heroic accounts. While their contributions were significant, these Sherpas weren’t officially recognised in the expedition's records.

This omission reflects a broader historical trend where the vital roles of Sherpas were often underacknowledged. Even photographs credited to climbers often involved Sherpas operating cameras, highlighting their invisible but indispensable expertise. Their loss was treated as a noble “sacrifice” to an imperial mission. In truth, British climbers couldn’t have approached Everest without the labour and wisdom of Himalayan people.

The 1922 expedition was also a media spectacle. Photographer John Noel produced a silent film and lecture tours presenting Everest as a stage for British endurance and destiny, blending dramatic footage with exotic props and music. The John Noel Everest movie gave the mountain an almost spiritual quality for postwar Britain, turning it into a symbol of national strength.

It also distorted reality: The Sherpa who climbed Mount Everest with the British were cast as loyal assistants, while their crucial skills in surviving at altitude made them unacknowledged experts. For centuries, Himalayan peoples lived and worked in extreme environments, long before Europeans arrived, but their expertise was hidden under the shadow of the empire.

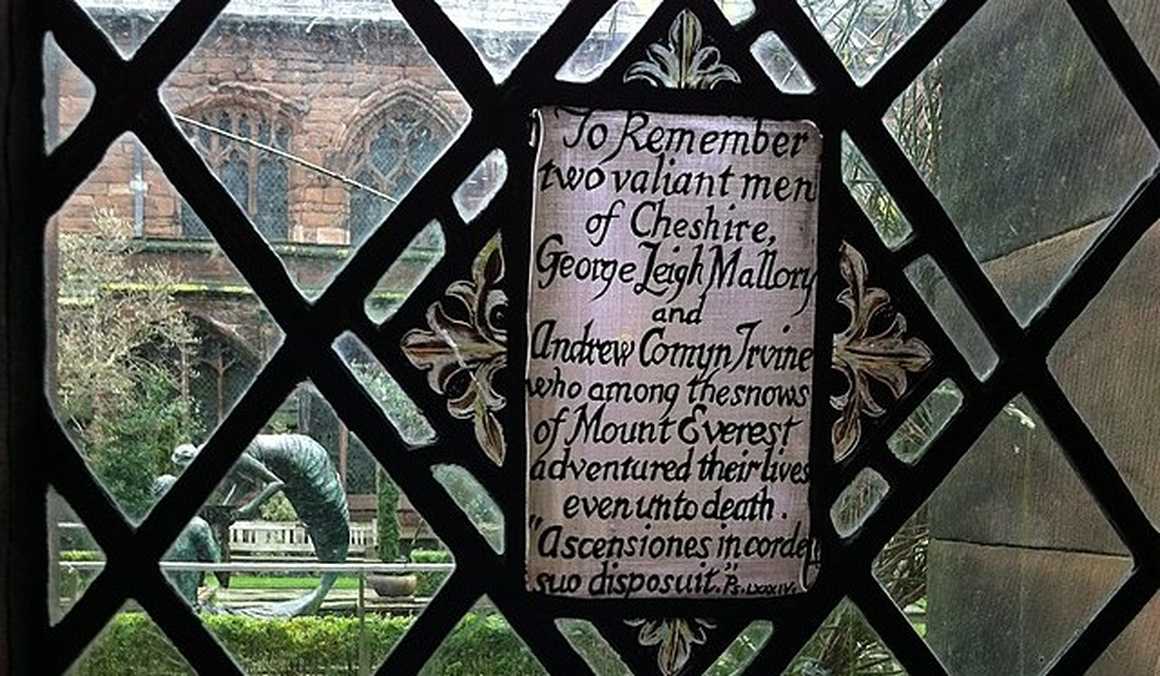

1924 - Mallory and Irvine disappear

The 1924 Everest Expedition was led by Edward Norton. It also included the climbers George Mallory and Andrew Irvine, as well as Noel Odell, Howard Somervell, and Geoffrey Bruce. The Himalayan team, Ang Tshering, Norbu Yishe, Lhakpa Chjedi, and Semchumbi were experienced high-altitude porters, and were critical to the team's progress. Approaching Everest via Tibet and the North Col route again, they established a series of high camps using Sherpa support and attempted acclimatisation through repeated climbs.

On 8 June, Mallory and Irvine made their summit push, last seen by Noel Odell at an estimated 8,600m before disappearing into cloud, leaving open the mystery of whether they reached the summit nearly thirty years before the confirmed first ascent in 1953. Expedition leader in 1924, Norton set a no-oxygen altitude record of 8,570m. His cautious style contrasted with Mallory’s boldness, shaping debates on oxygen use and Everest’s climbability.

Even here, the story remained one of British courage, despite eight porters accompanying the team to high camps, carrying oxygen cylinders (which, at the time, weighed 14.5kg) and provisions. Some porters turned back earlier; others stayed with Odell, supporting him at Camp V.

The sherpas on the 1924 expedition are now part of the historical record, but the names of many other porters were lost. Sherpas shouldered the same (if not more) risks as the British mountaineers, but their names seldom appear in expedition narratives despite their proximity to the critical stages. George Mallory himself noted in letters that the team couldn’t have reached the high passes or mapped the northern approaches without sherpa support.

1933 - 1938: Lesser-known early Everest peak climb attempts

The British commitment to conquering Everest remained unwavering after the 1922 and 1924 tragedies, although a hiatus ensued for the following nine years, due to geopolitical tensions and logistical challenges, including Tibet's closed borders.

In 1932 the Dalai Llama granted permission to approach the mountain from Tibet in the north, on the condition that all the climbers were British. So in 1933, the Royal Geographical Society (RGS), in collaboration with the Alpine Club, initiated the next British attempt. The Mount Everest Committee, a joint body formed by these organisations, coordinated and financed all pre WWII expeditions to Everest.

1933 - A return to the mountain

This team included four British Mountaineers - Frank Smythe, Eric Shipton, Lawrence Wager, Percy Wyn-Harris - and was led by Hugh Ruttledge, all of whom were part of the 1924 expedition. Also included was Karma Paul, a Tibetan interpreter fluent in multiple languages, who had accompanied six early British Everest expeditions (including 1924). Ang Tharkay was also involved in this expedition, one of the most respected Sherpa climbers of the pre-WWII Everest era. Known for his strength, judgment, and loyalty, he often carried loads higher than many European climbers and provided critical guidance on dangerous sections of the route. Porters, supplies and transport were organised in Darjeeling and the team established camps on the northern side of Everest. Smythe, Wager, and Wyn-Harris reached approximately 8,570 m, but failing weather and snow conditions forced them to retreat.

1936 - Everest trekking learning curves

Following another reconnaissance expedition in 1935, designed to establish more research after the failure of previous summit attempts, the 1936 expedition was again led by Hugh Ruttledge. Despite advice against another massive scale expedition, 30 sherpas were employed, including experienced sirdars Lewa and Nursang, who had also been on the 1933 expedition. A further supply chain of over 400 porters carried loads from Darjeeling to the Tibetan plateau.

However, severe monsoon snows hampered access and the heavy snowfall made route preparation difficult. Prolonged storms prevented higher camps from being stocked with oxygen and food, which left some of the team idle at high altitude, and increased incidences of frostbite and illness. Despite their best efforts, a summit push became impossible, and the expedition was abandoned.

1938 - The last pre-war Everest summit push

The 1938 expedition, led by Bill Tilman, was deliberately small-scale. The Mount Everest Committee underwrote a modest budget of £2,360 (versus £10,000 in 1936) and insisted on minimal publicity. The press and public were no longer interested, and, at a time of pre war hardship, such things were seen as extravagant.

Sherpa involvement again included Ang Tharkay as sirdar, Tenzing Norgay among the sherpas, and Karma Paul as interpreter/factotum. Logistics were austere: basic food rations (soup, porridge), few supplies, no radios. They couldn’t have foreseen the monsoon arriving early, or the deep powder as a result of this, above Camp VI. Summit attempts were unviable, and climbers reached 8,300m but were forced to turn back for safety.

Mount Everest summit attempts, post WWII and beyond

1953 - The first successful Everest summit climb

The imbalance of Sherpa/British Mountaineering notoriety began to shift in 1953, when Edmund Hillary reached the summit alongside Tenzing Norgay, a Sherpa whose decades of experience made him one of the world’s greatest mountaineers. Though Britain celebrated the climb as a national triumph, Norgay’s role was too visible to ignore, and his fame signalled a turning point.

Logistics on the 1953 expedition included 350 porters and 20 sherpas. Post-war advances in equipment for climbing Mount Everest aided the summit success and enabled the team to plan carefully staged camps.

Advances included:

- Lightweight aluminium climbing gear

- Reliable bottled oxygen

- High-altitude clothing

- Improved nutrition

Earlier summit bids faltered, but Hillary and Tenzing succeeded on May 29, using the South Col route.

1963 - The first American ascent of Mount Everest

The 1963 U.S. expedition, led by Norman Dyhrenfurth, was a large-scale, government-backed effort involving hundreds of sherpas carrying loads, fixing ropes, and establishing camps. Jim Whittaker, guided by Sherpa Nawang Gombu (Tenzing Norgay’s nephew), summited via the South Col route with oxygen. Days later, Tom Hornbein and Willi Unsoeld completed a bold traverse of Everest via the previously unclimbed West Ridge, descending by the South Col, an extraordinary feat. The expedition proved American capability on Everest but also underscored the indispensability of the Everest sherpa. Gombu became the first Sherpa to summit twice, breaking ground in demonstrating Sherpa leadership on technical ascents.

1978 - The first ascent of Everest without supplemental oxygen

In 1978, Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler made the momentous first ascent of Mount Everest without supplemental oxygen, using the South Col route. Their success overturned long-standing medical consensus that Everest’s summit was impossible without oxygen. Sherpas were instrumental in load carrying and camp preparation, though the final push was made without them.

This ascent also marked a philosophical shift toward smaller, lightweight expeditions. Messner later credited Sherpa endurance as inspiration for their attempt, acknowledging their adaptation to altitude. The climb proved the human body could endure Everest’s “death zone” unaided, reshaping mountaineering ethics and future strategies for high-altitude climbing.

But not using oxygen to climb Everest is controversial. Even today mountaineers argue that claiming a “reshaping of ethics” oversimplifies ongoing debates about safety, commercialisation, and reliance on support teams at extreme altitude.

1996 - An Everest disaster

In May 1996, commercial guiding reached a crisis when storms struck crowded summit bids. Expeditions led by Rob Hall and Scott Fischer lost multiple climbers, including themselves, in blizzard conditions.

Sherpas played critical roles in rescues, guiding exhausted clients down in the storm and carrying oxygen to stranded climbers. Key sherpas included Sardar Ang Dorje Sherpa, who led rescue efforts and assisted in evacuating survivors; Lopsang Jangbu Sherpa, who was sadly later killed in a separate avalanche in September 1996; and Ngawang Topche, who suffered from high-altitude pulmonary oedema while ferrying supplies and died in June 1996.

Logistics of commercial climbing - fixed ropes, staged oxygen caches, and strict client management - broke down under overcrowding and deteriorating weather. The tragedy, which killed eight in a single storm, exposed the risks of Everest trekking commercialisation but also highlighted sherpa bravery and their growing, underacknowledged role in life-saving mountain rescues.

2025 - Kami Rita Sherpa’s record 31st summit of Everest

On 27 May 2025, Sherpa guide Kami Rita broke his own world record by summiting Everest for the 31st time. The climb was part of a broader, 22 member Indian Army mountaineering programme, designed to train soldiers in high-altitude operations and survival skills.

With assistance from 27 other sherpas, Kami Rita ascended via the traditional Southeast Ridge (South Col route), managing logistics and guiding clients and Nepalese soldiers. The climb was smooth weather-wise compared to earlier seasons, but the sheer frequency of his ascents highlights sherpas’ enduring physical resilience and expertise in navigating the mountain’s hazards.

100 years of Mount Everest climbing history

The risks of summiting Everest remain profound. Sherpas continue to fix ropes and ladders through the Khumbu Icefall, carry heavy loads, and navigate zones most climbers traverse only once, their labour underpinning the entire altitude climbing industry, while exposing them to disproportionate risk.

Yet these same mountains have brought opportunity: tourism and expeditions have transformed local sherpa communities, bolstering trade, education, healthcare, and leadership in guiding and trekking enterprises. From Mallory’s North Col to today, Everest tells a dual story - of enduring risk and of resilience, recognition, and the vital legacy of sherpa expertise on mountains. Sherpas and Mount Everest are inextricably linked, and my my, aren’t we grateful for that!