Learn how to acclimatise at high altitude and prevent and manage altitude sickness

Acute mountain sickness (AMS or altitude sickness) is a very real problem when trekking at high altitude. Left unchecked, it can quickly turn a thrilling adventure into a miserable struggle. In severe cases, it becomes dangerous.

In this article, we provide an in-depth guide on high altitude acclimatisation, including how to reduce the chances of altitude sickness and how to recognise it when it happens. Plus, we provide guidance on managing altitude sickness if it occurs.

Disclaimer: Whilst the information we provide is as reliable as possible, we’re not medical experts. This article is an information resource only and shouldn't be relied upon for any medical diagnostics or treatment. Seek the advice of a qualified doctor if you have any medical issues that might be exacerbated by high altitude.

What is high altitude acclimatisation?

High-altitude acclimatisation describes how your body adjusts to decreasing oxygen levels at higher elevations.

At altitude, the air is thinner, which means each breath you take delivers less oxygen than you are used to. Acclimating properly helps your body adjust so you can keep moving, thinking clearly and feeling well.

By increasing altitude gradually, taking rest days and paying attention to how you feel, you give your body the time it needs to adjust and enjoy being at high altitude.

The relationship between air density, oxygen and altitude

To understand high-altitude acclimatisation, it helps to know how altitude, air density and oxygen interact. As you go higher above sea level, it isn’t the amount of oxygen in the air that changes, but how easy it is for your body to access it.

At sea level, oxygen makes up about 21% of the air, and the barometric pressure is roughly 760 mmHg.

Note: Barometric pressure is the weight of the air pressing down on you from the atmosphere above. It’s a measure of how much force the air exerts at a given altitude.

As you climb higher, that percentage of oxygen stays almost the same (at least until extremely high altitudes). What does change is the air pressure. As altitude increases, the air becomes thinner and less dense.

Thinner air means the oxygen molecules are more spread out. There’s still plenty of oxygen around you, but with less pressure, those molecules aren’t packed together as tightly.

That means every breath you take contains fewer oxygen molecules than it would at sea level.

For example, at around 3,600 metres (12,000 feet), barometric pressure drops to about 480 mmHg. That’s a big difference from sea level.

Top tip: To find out more about the science behind this, read this journal about oxygen at high altitude!

What is acute mountain sickness (AMS)?

Acute mountain sickness, or AMS, happens when your body struggles to adjust to lower oxygen levels at high elevations. Even fit, experienced hikers can experience AMS if they ascend too quickly or don’t give themselves enough time to acclimatise.

Symptoms usually start with headaches, fatigue, nausea, dizziness, or trouble sleeping. In some cases, mild symptoms can be easy to ignore, but if left untreated, AMS can progress to more serious conditions like high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) or cerebral edema (HACE). We look at these in more detail later.

Note: Pulmonary edema and cerebral edema are spelled differently in the UK (oedema), but they mean the same thing.

AMS is surprisingly common. For example, in Colorado, studies show that around 25% of visitors sleeping at altitudes above 2,450 metres (8,000 feet) experienced symptoms of AMS.

The likelihood of experiencing AMS increases the higher you climb and the faster you ascend, which is why proper acclimatisation, pacing and monitoring are so important.

By understanding AMS, recognising early symptoms and acting quickly, trekkers can reduce their risk and make high-altitude adventures safer and more enjoyable.

How to spot altitude sickness

Mountaineers usually divide AMS into three levels: mild, moderate and serious. Knowing the signs at each stage can help you identify it early and take action before it becomes dangerous.

Let’s look at each level in more detail.

Mild symptoms of altitude sickness

Mild AMS is quite common and can affect even fit, experienced trekkers. Symptoms might feel like a typical hangover or flu, but they signal that your body is struggling to adjust to thinner air.

Look out for:

- Headaches. Often dull at first but persistent, especially at the front or sides of the head.

- Fatigue or unusual tiredness. You may feel unusually drained after normal activity.

- Nausea or loss of appetite. Even foods you normally enjoy might feel off.

- Trouble sleeping. Difficulty falling asleep or restless nights are common at altitude.

- Dizziness or lightheadedness. Feeling unsteady or woozy is a sign your brain isn’t getting enough oxygen.

If you feel the onset of any of these symptoms, let your guides and fellow trekkers know.

Moderate symptoms

If mild symptoms are ignored, they can progress to moderate AMS. At this stage, your body is struggling more significantly. Symptoms include:

- Worsening headache. Pain that doesn’t improve with rest, hydration, or over-the-counter painkillers.

- Strong nausea or vomiting. Persistent nausea can make it hard to stay hydrated or eat.

- Shortness of breath at rest. Even when sitting or lying down, you may notice your breathing feels laboured.

- Weakness or fatigue. Walking or doing simple tasks feels exhausting.

- Swelling (edema). Puffiness in the hands, feet, or face occurs when fluid starts to leak from blood vessels due to lower oxygen levels.

If moderate symptoms get worse or don’t improve after a day, you’ll need to descend to a lower altitude if you can. The NHS website recommends around 300 to 1,000 metres lower. If you’re travelling with a guide (like on a Kandoo adventure), they can advise you on the best course of action.

Serious or severe symptoms

Serious AMS is dangerous and requires immediate action, often descent to a lower altitude or emergency care. Watch for:

- Severe headaches. Intense pain that doesn’t respond to altitude sickness medication or rest.

- Extreme nausea or vomiting. This can lead to dehydration and worsen oxygen delivery to your body.

- Confusion or loss of coordination. Difficulty walking straight, stumbling or feeling disoriented signals your brain is under oxygen stress.

- Fluid in the lungs (high-altitude pulmonary edema, or HAPE). Symptoms include severe shortness of breath, persistent coughing, rattling in the lungs or blue lips and fingers.

- Fluid in the brain (high-altitude cerebral edema, or HACE). Extreme confusion, drowsiness, hallucinations or difficulty staying awake are life-threatening signs.

If you notice any moderate or serious signs, stop ascending immediately. Rest, hydrate and if symptoms persist or worsen, descend to lower altitude without delay. Acting early is the best way to protect yourself and enjoy your trek safely.

What happens if you experience severe altitude sickness?

The two most notable conditions associated with severe AMS are HAPE and HACE. HAPE occurs when fluid leaks into your lungs through the capillary wall, and HACE occurs when fluid seeps into your brain.

Both conditions are extremely dangerous and usually occur from ascending too quickly or spending too long at high altitude.

Here’s what each condition means:

High-altitude cerebral edema (HACE)

Fluid builds up in your cranium and forces your brain tissue to swell. Here are the symptoms to look out for when identifying HACE:

- Hallucinations

- Disorientation

- Memory loss

- Coma

- Severe headaches that persist (even when medication is taken)

- Loss of coordination (also known as ataxia)

Generally, HACE symptoms typically appear at night. HACE is extremely dangerous and life-threatening, so you mustn’t wait until morning to seek assistance. Staying at altitude with HACE increases the likelihood of fatality.

Start descending immediately and seek medical support as early as possible.

High-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE)

HAPE is caused by a buildup of fluid in the lungs that prevents effective oxygen exchange and an adequate level of oxygen from entering your bloodstream.

Like HACE, HAPE occurs most frequently from ascending too high too fast. Here are the symptoms to look for when identifying HAPE:

- Very tight chest

- Extreme shortness of breath even when resting

- The feeling of suffocation (especially when sleeping)

- Extreme weakness and fatigue

- Hallucinations, irrational behaviour, and confusion

- A cough that brings up a white, frothy fluid

As with HACE, descending immediately is essential. You can also administer oxygen if available.

Side note: Emergency oxygen is carried by qualified guides on all Kandoo Adventures treks involving high-altitude.

When descending, make sure that the person suffering from HAPE does not exert themselves. A stretcher or helicopter evacuation is often the best course of action.

Once at the bottom, seek medical support immediately.

5 ways to reduce the risk of altitude sickness

The key to staying healthy at high altitude is giving your body the time and support it needs to adapt. By following a few proven principles, you can significantly reduce your risk of AMS and enjoy your trek or climb with more confidence and comfort.

1. Start small and work your way up

Avoid jumping straight to high altitude without giving your body time to adapt. If possible, spend time training for high altitude over a few weeks or months by trekking at lower elevations first so your body can get used to it.

If you’re new to high-altitude trekking, don’t rush. The slower you ascend, the more time your body has to adjust to the thinner air. A gradual approach significantly reduces your risk of developing altitude sickness.

Ideally, plan a route that allows you to climb high during the day and sleep at a lower altitude. This “climb high, sleep low” approach is one of the most effective ways to acclimatise. Spending long periods sleeping at high altitude places extra strain on your body.

It’s also important not to overexert yourself. Keep a steady pace that feels sustainable, even if it feels slower than you’re used to. At altitude, there’s less oxygen available, and pushing too hard only increases fatigue and stress on your body.

2. Keep well hydrated

Dehydration can make altitude symptoms worse and harder to manage. Drink regularly throughout the day, even if you don’t feel thirsty.

It's typically recommended to drink a minimum of three litres of water a day at high-altitudes. If you think this will be a challenge, start practicing before your trip so it won't be as difficult.

Avoid alcohol, stimulants, excessive caffeine, and smoking, as these can interfere with sleep, worsen dehydration, and mask early symptoms of altitude sickness.

3. Use the right medication

Medication can be incredibly helpful when spending time at high altitudes. It can relieve pain and generally improve your overall experience.

Here are some of the common options:

Acetazolamide (Diamox)

- What it does: Helps your body adjust faster to higher altitudes by speeding up breathing and improving oxygen delivery.

When to use it: Often started a day before ascent and continued for a few days at higher altitudes.

Note: In the UK, Acetazolamide is a prescription-only medication and you should speak with a doctor if you’re planning a trip to high-altitude.

Dexamethasone

- What it does: A steroid used to treat severe AMS or high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE). It reduces swelling in the brain caused by low oxygen.

- When to use it: Only for serious cases and usually under medical guidance. Not meant for routine prevention.

Ibuprofen or other painkillers

- What it does: Relieves headaches and minor aches that often come with mild AMS.

- When to use it: As needed, but it doesn’t prevent altitude sickness; it only treats the symptoms.

Anti-nausea medication

- What it does: Helps reduce nausea and vomiting caused by AMS, making it easier to stay hydrated and eat.

- When to use it: Useful for mild to moderate AMS, especially if symptoms are interfering with sleep or appetite.

If you start experiencing any of these symptoms when you are at high-altitude, you should speak with your guiding team as they have a huge amount of experience and will support and monitor you.

Note: Speak to your doctor before travelling if you want to obtain any medication ahead of your trip, and to find out more about the potential side effects. Some of these medications can only be obtained on prescription and must be administered by a healthcare professional.

4. Take regular rest days

Rest days are a crucial part of acclimatisation. Remaining at the same altitude for an additional day gives the body time to acclimatise to lower oxygen levels by enhancing breathing efficiency and initiating increased red blood cell production.

Even if you feel strong and symptom-free, rest days help reduce hidden fatigue and lower your risk of AMS later on.

A good rest day doesn’t mean doing nothing. Light walks, gentle stretching, or short hikes to a slightly higher point can all support acclimatisation without overloading your body.

5. Hire a mountain guide

Hiring an experienced mountain guide can significantly reduce the risks of trekking at high altitude, especially if you’re new to it or trekking in remote regions.

Some regions actually require you to explore with a guide. Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, the Inca Trail in Peru and many trekking regions in Nepal are a few examples.

Guides are trained to recognise early signs of altitude sickness, often before trekkers notice symptoms themselves. A good guide will manage pacing, encourage regular breaks, and adjust the itinerary if conditions or health issues arise.

They’ll also know when it’s safer to stop ascending, add an extra rest day, or descend if necessary.

Beyond safety, guides can improve the overall experience. They handle route finding, logistics, and understand local conditions. As a result, you can focus on the trek while knowing someone experienced is looking out for your well-being at altitude.

Joining a Kandoo adventure? We’ve got you covered!

When it comes to altitude, our guides keep a close eye on every member of the group to make sure your body copes with the changes.

During high-altitude treks, you’ll receive a daily health check that includes monitoring your pulse rate, blood oxygen saturation levels and overall acclimatisation progress.

Here’s what Hannah had to say about her Kandoo guide and how they helped members of her group manage altitude sickness:

“Robert's expertise was second to none! He was so patient and calm even when those who fell ill from altitude couldn't make it, he knew exactly what to do and dealt with it so professionally. His knowledge brought so much ease and trust to the group and we genuinely wouldn't have done so well without him!” - Hannah, Trustpilot.

What to do if you experience altitude sickness

If you start to experience symptoms of altitude sickness, it’s important to act early. Ignoring the signs or pushing on can make symptoms worse and increase the risk of serious complications.

Stop ascending

As soon as symptoms appear, don’t continue climbing. Stay at your current altitude and give your body time to recover. Many mild symptoms improve with rest and hydration.

Rest and hydrate

Take it easy and drink plenty of fluids. Avoid alcohol and sleeping pills, as these can interfere with breathing and make symptoms worse.

Treat the symptoms

Mild headaches or nausea can sometimes be managed with painkillers or anti-nausea medication. Remember, medication may ease symptoms, but it doesn’t fix the underlying problem.

Descend if symptoms don’t improve

If symptoms persist after rest or begin to worsen, descend to a lower altitude. Even a descent of a few hundred metres can lead to noticeable improvement.

Seek medical help for severe symptoms

Severe headache, confusion, trouble walking, shortness of breath at rest, or persistent vomiting are medical emergencies. Descend immediately and seek professional medical assistance.

Acting quickly and listening to your body is the safest way to manage altitude sickness and protect your health at high altitude.

Altitude sickness FAQs

How does your body adapt at higher altitude?

Your body adapts in four key ways:

- Breathing faster and more deeply so your lungs take in more oxygen to compensate for the thinner air.

- Increasing your red blood cell count, allowing your blood to carry higher amounts of oxygen

- Boosting pressure to your pulmonary capillaries, which forces blood into parts of your lungs not used when breathing at sea level

- Producing an enzyme (2,3‑bisphosphoglycerate) in greater quantity that causes oxygen to be released from haemoglobin to the blood tissue

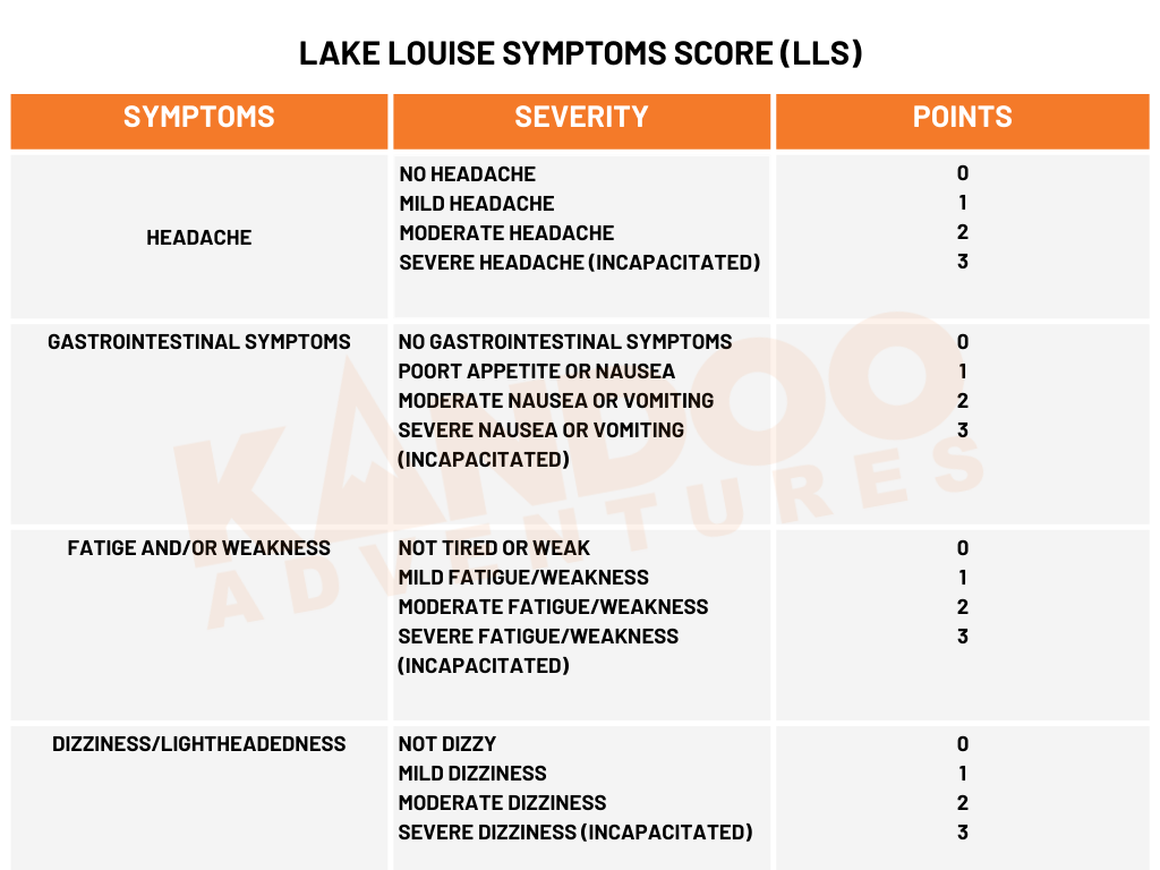

What is the Lake Louise altitude sickness scorecard?

The Lake Louise Score is a system for identifying and assessing AMS at high altitude. It provides a simple, structured way to track symptoms and understand how well your body is coping as you ascend.

The scorecard focuses on common AMS symptoms such as headache, nausea, fatigue, dizziness and sleep disturbance. Each symptom is rated based on its severity, and the combined score helps indicate whether AMS is mild, moderate or more serious.

Here’s how it works:

Scoring between 3 and 7 is a sign of mild to moderate altitude sickness, while scoring above 7 is severe.

Because it’s easy to use and doesn’t require medical equipment, the Lake Louise Score is commonly used by trekkers, guides and expedition teams in remote environments. While it’s not a diagnostic tool on its own, it’s a valuable way to spot problems early and make safer decisions about rest, ascent or descent.

Fun fact: On all of our treks and summit climbs, our guides take your Lake Louise score each day, along with measuring your pulse and SpO₂ (oxygen saturation).

When does altitude start to have an impact?

People can feel altitude sickness at 2,500 metres (8,200 feet) above sea level. As you go higher, the risk increases.

Symptoms become more common and more pronounced above 3,000 metres (10,000 feet). This is why gradual ascent and proper acclimatisation become increasingly important the higher you climb.

What is blood oxygen saturation?

Blood oxygen saturation (often written as SpO₂) is how much oxygen your red blood cells are carrying compared to their maximum capacity.

SpO₂ is shown as a percentage. At sea level, a healthy person will usually have an oxygen saturation of around 95 to 100%.

As you go to higher altitudes, blood oxygen saturation naturally drops. This isn’t because there’s less oxygen in the air overall, but because the air pressure is lower. With less pressure, oxygen molecules are more spread out, which makes it harder for oxygen to move from your lungs into your bloodstream.

At around 2,500 metres, many people will see their oxygen saturation fall into the high 80s or low 90s. As altitude increases further, those numbers can drop even more. Some research shows declines of between 26 and 29% at an altitude of 4300 metres!

This reduction is one of the main reasons people feel short of breath, tired or develop symptoms of altitude sickness.

Over time, acclimatisation helps improve oxygen delivery. Your breathing becomes more efficient, your heart pumps faster, and your body produces more red blood cells. While your oxygen saturation may never return to sea-level values at altitude, these adaptations help your body function more efficiently with the oxygen available.

Fun fact: Monitoring blood oxygen saturation (often with a pulse oximeter) can be a useful way to track how well your body is coping at altitude.

What is the acclimatisation line?

The acclimatisation line is the safe rate of ascent that allows your body enough time to adjust to thinner air and lower oxygen levels. Think of it as a “guide” for how high you can climb each day without overloading your body.

Here’s an example: If your acclimatisation line is at 3,000 metres, you need to spend a day or two at that altitude level to let your body acclimatise.

After several days, your new acclimatisation line might be 3,750 metres. This means that you can ascend to 3,700 metres without AMS symptoms.

Note: If you ascend above the acclimatisation line too quickly, your risk of altitude sickness increases significantly.

High-altitude trekking is amazing, but your body needs time to adapt. Gradual ascent, rest days, hydration and knowing the signs of AMS all help reduce risks.

And trekking with an experienced guide? That takes safety to the next level. They monitor your health, manage pacing and respond quickly if symptoms appear.

On a Kandoo adventure, our knowledgeable guides provide daily health checks, track acclimatisation and ensure you can focus on the experience. Book your Kandoo trek today and explore high altitudes with confidence and expert support!